Introduction

Breastfeeding is a natural source of nutrition for newborns. Breastmilk is the preferred nutrition, providing all the nutritional ingredients a newborn requires (R. F. Durham & Chapman, 2019). It contains vitamins, nutrients, and immunity to help newborns grow and develop properly. These benefits support the idea of newborns being exclusively on breastmilk during their early development. Early breastfeeding initiation prompts breastmilk production and facilitates lactogenesis. The establishment of breastmilk supply is crucial to breastfeeding success and has been shown to decrease newborn mortality risk (WHO, 2018). However, a newborn must be able to be placed on the breast to stimulate milk production and build an adequate supply.

Early initiation of breastfeeding means the baby can latch on to the breast and start breastfeeding within one hour after birth (WHO, 2018). Immediate and uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact (SSC) should be promoted and encouraged as soon as possible after delivery to facilitate the newborn’s natural rooting reflex, which imprints the behavior of looking for the breast and suckling (Bigelow & Power, 2020). Skin-to-skin contact (SSC) is defined as placing a newborn in a prone position on the mother’s bare chest, and this contact should be uninterrupted for at least one hour (Allen et al., 2019). Outlined in the WHO Guideline Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative - Step 4 recommendation (BFHI - Step 4), skin-to-skin contact (SSC) and early initiation of breastfeeding are interventions that work together to provide optimal maternal-newborn benefits. Skin-to-skin contact directly leads to early breastfeeding initiation as newborns naturally find their way to the breast and latch spontaneously. Mothers who want to breastfeed exclusively benefit from having breastfeeding support services in the first hours following delivery. Implementing recommendation BFHI-Step 4 increases a mother’s milk supply, and the successful production of milk is associated with longer breastfeeding duration and exclusivity (Sanchez-Espino et al., 2019).

Background

Recommendation Step 4 from the WHO (2018) Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (BFHI - Step 4) emphasizes the importance of immediate and uninterrupted SSC between mother and newborn and supports breastfeeding initiation within the first hour after birth (See Box 1). This step is critical because early SSC stimulates the newborn’s natural rooting reflex, promotes suckling, and supports the colonization of the infant’s microbiome. It also helps regulate the newborn’s body temperature and reduces the risk of hypoglycemia and infant mortality.

Early suckling activates hormonal responses that stimulate lactogenesis and the establishment of an adequate milk supply, both essential for long-term breastfeeding success (H. A. Durham & Chapman, 2023). The early intake of colostrum, rich in antibodies and nutrients, offers immediate immune protection and nutritional benefits. Supporting recommendation BFHI-Step 4 aligns with global efforts to improve maternal and newborn health outcomes. By facilitating immediate SSC and early breastfeeding, healthcare providers can significantly enhance breastfeeding rates and infant survival, especially in resource-limited settings.

Breastfeeding is a fundamental method of newborn feeding. The Office of the Surgeon General’s (2011) Call to Action to support breastfeeding was made to improve the efforts of public health impact, decrease health care inequities that affect some maternal-newborn dyads, and increase support in employment and community settings. Additionally, the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) launched the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative to motivate healthcare facilities to implement the ten steps to successful breastfeeding (WHO, 2018). The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding comprise evidence-based practices that increase breastfeeding initiation, duration, and maintenance (WHO, 2018).

Despite known benefits and for a variety of reasons, breastfeeding is not consistently initiated immediately after delivery. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2021), most mothers want and try to breastfeed their newborn; however, desire alone is not enough, as they face multiple and complex nursing workflow barriers that decrease early breastfeeding initiation and continuation.

The nursing workforce plays a vital role in supporting a mother’s desire to breastfeed. Nurses are often the first and most consistent source of education and encouragement during the prenatal, birth, and postpartum periods. Their support significantly increases breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates (McFadden et al., 2017). Trained nurses help mothers with early breastfeeding practices such as SSC, proper latch techniques, and managing common challenges. Positive, evidence-based guidance from nurses boosts maternal confidence and reduces early weaning (Patel & Patel, 2016). In contrast, a lack of training or understaffing can hinder breastfeeding outcomes (Taylor et al., 2021).

Health systems that invest in breastfeeding education for nurses and staff, such as using the WHO’s (2018) Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), consistently see better breastfeeding success. Barriers to breastfeeding involve the inability of nurses or staff to facilitate SSC, lack of breastfeeding knowledge, newborns being placed almost immediately on the radiant warmer and then promptly swaddled, and other disruptions, such as medication administration and newborn assessment (Allen et al., 2019).

The CDC (2022) emphasized that nurses play a key role in supporting mothers with breastfeeding, helping to increase early initiation and promote exclusive breastfeeding after hospital discharge. These CDC breastfeeding strategies direct nurses to promote early breastfeeding initiation within the first hour after delivery by providing mothers with breastfeeding support, education, and encouragement. Healthcare organizations, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN), American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), support early breastfeeding initiation interventions because they promote longer duration of breastfeeding, increased exclusivity, and sustained breastfeeding practices (R. F. Durham & Chapman, 2019).

Breastfeeding has been shown to be more cost-effective than formula or other feeding methods as it reduces the newborn’s susceptibility to infectious and chronic diseases (Binns & Lee, 2019). The Healthy People 2030 objective on breastfeeding has set a baseline breastfeeding rate of 76.1% and aims to achieve a goal of 81.9% (US DHHS, 2022). Although efforts to promote breastfeeding have been at the forefront of current research and quality improvement initiatives, breastfeeding maintenance remains a significant issue.

Nurses’ attitudes towards breastfeeding play a role in determining which method of newborn feeding will be chosen (Weshahy et al., 2019). A significant gap in early breastfeeding initiation arises from systemic issues within healthcare settings. Nurses are often overburdened, and staffing levels may be insufficient to provide timely, hands-on support for every mother immediately after birth. This lack of consistent support can delay or prevent early breastfeeding initiation. According to Karimi et al. (2020), such inconsistencies in practice directly hinder the establishment of exclusive breastfeeding, which is essential for optimal infant health outcomes.

It is essential to implement evidence-based breastfeeding practices to promote early and continuous breastfeeding. BFHI-Step 4 recommendation supports immediate postnatal care by facilitating SSC followed by early breastfeeding initiation as soon as possible after birth. The immediate postpartum period is crucial for establishing a robust foundation for breastfeeding initiation and milk supply. Breastfeeding support is vital to breastfeeding success and achieving optimal maternal-newborn outcomes.

Project Objective

To address the low rates of exclusive breastfeeding at the clinical site, a quality improvement project was designed involving the adoption of the BFHI-Step 4 recommendation to facilitate immediate and uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact and support mothers to initiate breastfeeding as soon as possible after birth. This project aimed to implement the BFHI-Step 4 recommendation to support mothers wanting to exclusively breastfeed their newborn. The overall goal was to increase the exclusive breastfeeding rate from 38% to 50% over a 4-week period.

Methods

Setting

This quality improvement initiative was conducted at a 377-bed suburban hospital located in Southern California. The Maternal–Child Health Department encompassed integrated labor and delivery, postpartum, and neonatal intensive care units. The labor and delivery service operates 15 suites that accommodate triage, antepartum, and intrapartum care, managing approximately 300 births per month (≈3,600 annually). A multidisciplinary team of obstetricians, certified nurse-midwives, registered nurses, and allied specialists provides comprehensive care focused on optimizing maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Project Design and Frameworks

This project utilized a quantitative, quasi-experimental quality improvement project design. The clinical question for this project was to examine the degree to which the implementation of the BFHI-Step 4 recommendation from the WHO (2018) Guidelines Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) impacted exclusive breastfeeding rates when compared to current practice among adult postpartum women in a labor and delivery unit within an acute care hospital in Southern California.

This QI project was guided by Kurt Lewin’s (1947) Change Theory and Nola Pender’s Health Promotion Model (2014), while adhering to the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines (Ogrinc et al., 2016). Lewin’s Change Theory provided a systematic approach to driving organizational change in three stages: unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. In the unfreezing phase, stakeholders were engaged to identify and promote the need for change of implementing BFHI-Step 4 recommendation - the immediate and uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact and support mothers to initiate breastfeeding as soon as possible after birth. During the changing phase, the evidence-based intervention of BFHI-Step 4 recommendation, focusing on health promotion and behavior change, aligned with Pender’s theory, was introduced to the nursing staff. The BFHI-Step 4 intervention was aimed at improving exclusive breastfeeding rates. The final phase, refreezing, focused on embedding this new practice into the daily routines and ensuring its sustainability through ongoing support and training.

Participants and Measures

Participants for this QI project were 40 labor and delivery (L&D) nurses who facilitated early initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after delivery. The focus of the project was to assess the impact of incorporating the BFHI-Step 4 recommendation into nursing interventions, specifically evaluating its effect on exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates. Early breastfeeding data were extracted from the facility’s electronic health record (EHR) both before and after the intervention. Successful early breastfeeding initiation was defined as the newborn achieving a latch on at least one breast within the first hour of life, as documented by the nurse in the EHR. Exclusive breastfeeding rates were determined by documenting the absence of formula supplementation from delivery through discharge. Data collected from maternal-newborn charts included details on delivery, newborn feeding practices, and maternal demographics.

The QI project sought to examine the influence of nursing knowledge and attitudes on EBF rates. The L&D nurse participants were provided with training on breastfeeding practices based on the WHO (2018) Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) Guideline. Following this training, the nurses applied the knowledge and techniques learned in their clinical practice to support mothers in initiating and maintaining exclusive breastfeeding. The data collection process involved comparing a group of mothers who received care based on prior practice (preintervention) with a group of mothers who received early breastfeeding initiation support from the trained nurses during the four-week intervention period. By equipping nurses with education on the benefits of breastfeeding, the project aimed to enhance patient advocacy and support for breastfeeding, ultimately encouraging mothers to engage in exclusive breastfeeding during their hospital stay.

Intervention

The intervention for this quality improvement project was based on the BFHI-Step 4 recommendation, which focuses on supporting mothers to initiate breastfeeding as soon as possible after birth. The primary goal was to facilitate immediate and uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact (SSC) between mothers and newborns during the critical postpartum period. This practice was coupled with active support for early breastfeeding initiation, which is a vital step in promoting exclusive breastfeeding and improving infant health outcomes.

L&D nurses were provided with comprehensive education techniques for supporting early breastfeeding initiation, with a focus on the immediate postpartum period. This training emphasized the importance of SSC and the role of nurses in guiding mothers through the early stages of breastfeeding. Nurses were equipped with the knowledge and skills to assist mothers in positioning their newborns for a successful latch and to address any challenges that might arise during the initial breastfeeding attempt. By offering this support, nurses helped mothers feel more confident and informed about breastfeeding, empowering them to take an active role in their newborns’ nutrition and care. The intervention also emphasized the need for uninterrupted SSC to foster a positive breastfeeding experience and to enhance maternal-newborn bonding. This intervention attempted to create an environment that encouraged early, successful breastfeeding initiation.

Ethical Considerations

This project was deemed a quality improvement intervention in nature and, therefore, was not reviewed by the Institutional Review Board. The ethical principles of human subject protection and the project site’s policies were followed to ensure that patients’ privacy, confidentiality, and safety were maintained. Given the minimal risk to participants, as de-identified and aggregate data were utilized, written informed consent was not required.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data was extracted from the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) and compiled into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet by the Director of Maternal Child Health. The data included maternal demographics, such as age and ethnicity, and key clinical variables such as delivery time, birth weight, and the timing of SSC and breastfeeding initiation. The dependent variable, exclusive breastfeeding rates, was calculated based on the proportion of mothers who exclusively breastfed (i.e., no formula supplementation) from delivery through discharge. The data for the comparative and implementation groups were entered using numeric codes and study identifiers to ensure confidentiality. Data were then exported into the IBM SPSS version 28 for analysis, where frequency counts and range scores were used to check for missing data and outliers. Descriptive statistics were performed on demographic variables, with age analyzed using mean and standard deviation, and ethnicity using frequency counts and percentages.

For the data analysis, the independent variable was the implementation of the WHO (2018) BFHI-Step 4 intervention, and the dependent variable was the exclusive breastfeeding rates. The primary analysis employed a non-parametric chi-square test to assess the impact of the intervention on breastfeeding rates. This test was appropriate given the nominal nature of both independent and dependent variables. The chi-square test allowed for comparison between the two groups- those receiving the intervention and those receiving prior care. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05, and a p-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance. By applying this methodology, the investigator evaluated the effect of the BFHI-Step 4 recommendation intervention on exclusive breastfeeding outcomes in a non-randomized, quasi-experimental design.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The QI project drew data from two intertwined participant groups, Labor and Delivery (L&D) nurses and immediate postpartum patients, each with clearly defined eligibility parameters. The L&D nursing participants had to be registered nurses assigned to the hospital’s 15-suite Labor and Delivery unit, provide direct intrapartum or immediate-postpartum care, and voluntarily complete the 10- to 15-minute BFHI-Step 4 recommendation training sessions. Travel, agency, or cross-cover nurses, those on extended leave, and staff whose primary assignment was antepartum, postpartum, or the NICU were excluded to ensure that only clinicians consistently present during the intervention were evaluated. For the patient cohort, charts were included if the mother was ≥ 18 years old, delivered a live, term infant in the unit during the four-week baseline or four-week implementation windows, and had complete electronic documentation of skin-to-skin contact, latch timing, and feeding method from delivery through discharge. Mothers or newborns were excluded when circumstances precluded immediate skin-to-skin or breastfeeding—e.g., general-anesthesia cesarean with prolonged postoperative recovery, maternal contraindications to breastfeeding, multi-fetal gestation, major congenital anomalies affecting feeding, admission of the infant to the NICU, stillbirth, or incomplete feeding documentation. These criteria ensured that the analysis compared equivalent, clinically eligible dyads while capturing the full effect of the nurse-led BFHI-Step 4 intervention on exclusive breastfeeding rates in routine care.

Results

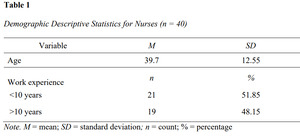

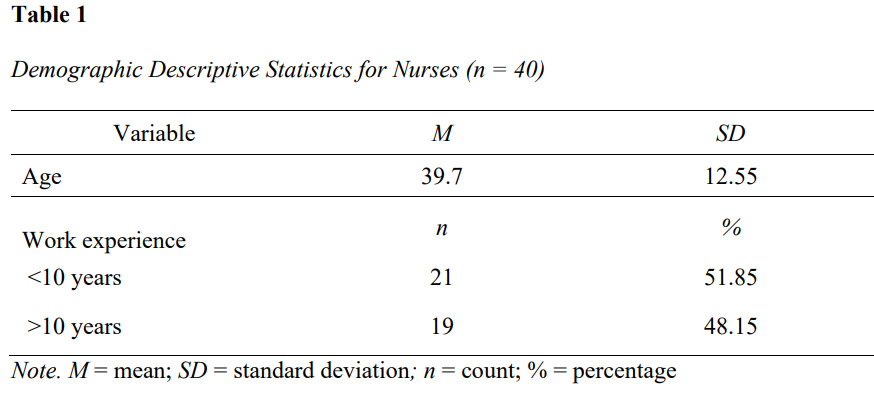

The participants for this QI project included registered nurses working in a labor and delivery unit of an acute care hospital in Southern California. Forty Labor & Delivery (L&D) nurses volunteered to participate in the QI project. Each participant attended a training session that lasted about 10 to 15 minutes, which described how to implement the BFHI-Step 4 recommendation. The Director of the Maternal Child Health Division provided demographic data for both L&D nurses and post-partum patients, along with exclusive breastfeeding rate information. The mean age was 39.7 (SD = 12.55). Most participants reported having less than ten years of nursing experience (n = 21, 51.85%). Nineteen participants (48.15%) had more than ten years of nursing experience. Most participants reported assisting with skin-to-skin contact (SSC) and exclusive breastfeeding initiated during the immediate postpartum period. About 75% of the nurses supported exclusive breastfeeding practices, and the remaining 25% supported combination feeding. All participants were female. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for nurses.

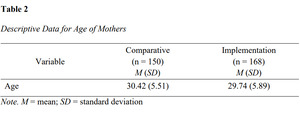

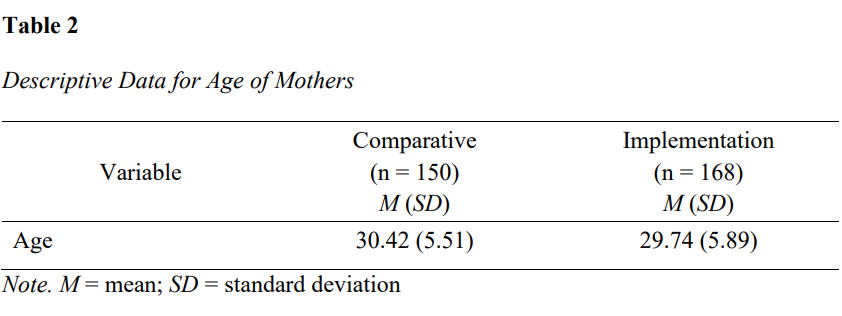

The outcome population for this project was post-partum patients admitted to the labor and delivery unit during the four weeks before and after implementing the WHO Guideline’s BFHI-Step 4 intervention. The total sample size was 318 postpartum patients (n = 150 in the comparative group and n = 168 in the intervention group). The mean age of mothers in the comparative group was 30.42 (SD = 5.51), ranging from 18 to 45, and in the implementation group, the mean age was 29.74 (SD = 5.89), with a range from 18 to 43. See Table 2 for descriptive data for age.

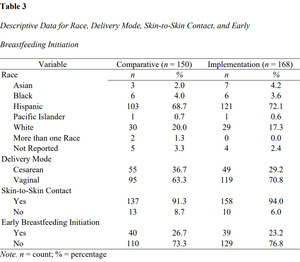

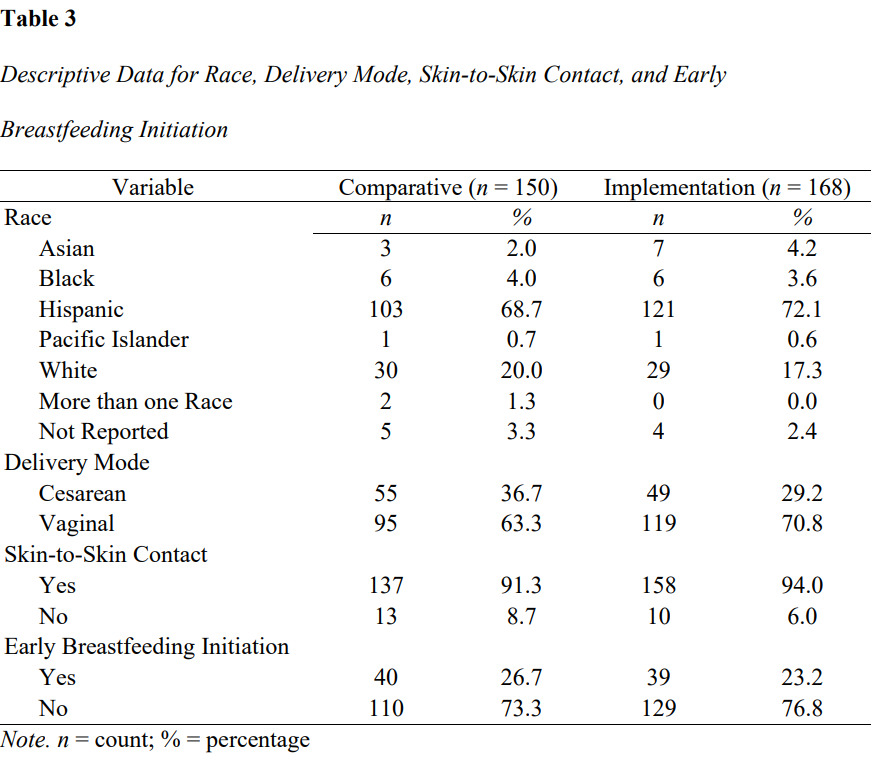

In Table 3, descriptive data are displayed for race, delivery mode, skin-to-skin contact, and early breastfeeding initiation for the comparative and implementation groups. There were three (2%) Asian women in the comparative group, which increased to seven (4.2%) in the implementation group. Black women were 4% (n = 6) of the comparative group, which decreased to 3.6% (n = 6) of the implementation group. Hispanic women were the most prevalent ethnicity in the comparative and implementation groups at 68.7% (n = 103) and 72.1% (n = 121). There was one Pacific Islander woman (0.7%) in the comparative group and one (0.6%) in the implementation group. Twenty percent of the comparative group identified as White (n = 30) compared to 17.3% (n = 29) of the implementation group. Two women (1.3%) identified as more than one race in the comparative group, but none (0%) identified as more than one race in the implementation group. Five women (3.3%) in the comparative group and four (2.4%) in the implementation group did not report a race.

Fifty-five women (36.7%) in the comparative group had a cesarean section, and 29.2% (n = 49) of the implementation group had a cesarean section. Vaginal birth was the most common mode of delivery for 63.3% (n = 95) of the comparative group and 70.8% (n = 119) of the implementation group. In the comparative group, 91.3% (n = 137) of the women performed SSC, and 8.7% (n = 13) of the women did not perform SSC. In the implementation group, 94% (n = 158) performed SSC and 6.0% (n = 10) did not. Early breastfeeding was initiated for 26.7% (n = 40) of the comparative group and 23.2% (n = 39) of the implementation group. Those not initiating early breastfeeding made up 73.3% (n = 110) in the comparative group and 76.8% (n = 129) in the implementation group.

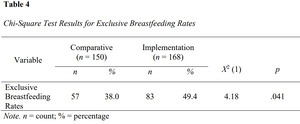

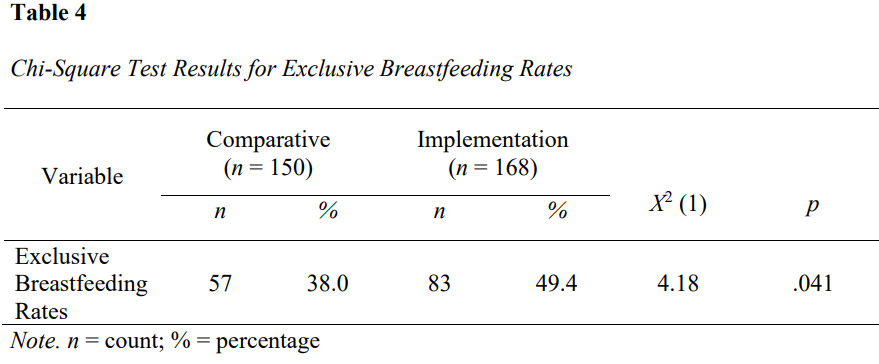

The results addressed the clinical question: To what degree does the implementation of the BFHI-Step 4 intervention impact exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates when compared to current practice among adult postpartum patients in an L&D unit? See Table 4 for chi-square test results. The results showed an increase in EBF rates from 38.0% in the comparative group (n = 57 out of 150) to 49.4% in the implementation group (n = 83 out of 168), χ2(1, N = 318) = 4.18, p = .041. The p-value was less than .05, which indicated that the increase in the EBF rates was statistically significant. The 11.4% increase in EBF rates was considered clinically significant, indicating a meaningful improvement in patient outcomes.

Conclusions

The findings of this QI initiative suggest that implementation of the World Health Organization’s (2018) Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative Step 4 (BFHI-Step 4) recommendation, which promotes immediate and uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact (SSC) and early initiation of breastfeeding, can significantly increase exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates after birth in a labor and delivery unit. Even though the goal EBF of 50% was not achieved, the 11.4% increase in EBF rates observed post-intervention was both statistically and clinically significant, reinforcing the value of structured nursing interventions in supporting breastfeeding outcomes (Allen et al., 2019; H. A. Durham & Chapman, 2023; Gray et al., 2021; WHO, 2018). This improvement underscores the critical role of labor and delivery nurses in influencing maternal behaviors through timely, evidence-based care practices in the immediate postpartum period.

The project adds to a growing body of literature indicating that SSC and early breastfeeding initiation are essential components of successful breastfeeding practices. Consistent with prior research (Allen et al., 2019; Karim et al., 2018, 2018; Sanchez-Espino et al., 2019; WHO, 2018), the results demonstrated that mothers who experienced early SSC and received nurse-facilitated breastfeeding support were more likely to initiate and sustain exclusive breastfeeding. These outcomes were achieved following a brief but targeted nurse education intervention, suggesting that even low-resource, scalable strategies can meaningfully affect patient care when grounded in evidence and theory. Nola Pender’s Health Promotion Model and Kurt Lewin’s Change Theory provided the theoretical foundation for nurse behavior change, which translated into improved maternal-newborn outcomes.

The project also highlighted the importance of ongoing nursing education and cultural competence in breastfeeding support. Although not all mothers in the intervention group achieved exclusive breastfeeding, the widespread adoption of SSC and early latch initiation among this cohort suggests increased awareness and engagement, both among nursing staff and patients. Nurse participants also shared qualitative feedback that emphasized a desire to expand education efforts across other units, such as postpartum and NICU, and to include prenatal provider involvement. These perspectives reinforce the idea that promoting EBF requires a comprehensive, system-wide approach that extends beyond labor and delivery and begins well before hospital admission.

From a systems perspective, this QI project demonstrates how nurse-driven evidence-based initiatives can be implemented within routine workflows without requiring extensive restructuring or resource investment. The positive outcomes observed further validate national and international recommendations encouraging immediate SSC and breastfeeding support as a standard of care (ACOG, 2021; CDC, 2022; WHO, 2018). By reinforcing the value of nurse education, workflow integration, and patient-centered communication, the project contributes to the broader goal of improving maternal-infant health outcomes and advancing public health priorities outlined in Healthy People 2030 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

Limitations

There were four main limitations to consider when interpreting the results of this quality improvement project. First, the project was conducted at a single labor and delivery unit within one suburban hospital in Southern California, which limits the generalizability of findings to other settings with differing patient populations, staffing structures, or organizational cultures. The small sample of nurse participants (n = 40), who voluntarily participated in the intervention, may have introduced selection bias, as those more interested in breastfeeding support were potentially more likely to engage.

Second, the project’s short duration—limited to a four-week pre-intervention and four-week post-intervention period—may not have captured the long-term effects of the BFHI-Step 4 implementation on exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates. A longer follow-up period may be necessary to determine the sustainability of the intervention and its influence on breastfeeding duration beyond hospital discharge.

Third, reliance on retrospective electronic health record data introduced the possibility of incomplete or inaccurate documentation, particularly regarding early skin-to-skin contact, latch timing, and feeding method. Variability in nurses’ charting practices, especially under high workload conditions, may have affected data consistency. Additionally, early breastfeeding initiation was self-reported by nursing staff and may not have always reflected real-time initiation or maternal-infant interactions with precision.

Finally, while anecdotal feedback from nurses suggested positive reception and perceived effectiveness of the intervention, the project did not include a formal evaluation of nurse knowledge retention or patient satisfaction, which could provide additional insight into intervention fidelity and impact.

Future initiatives may consider extending the project’s timeline, expanding to multiple sites, and incorporating longitudinal tracking of breastfeeding duration to assess sustained effects. In addition, enhancing interprofessional collaboration among physicians, midwives, and lactation consultants may strengthen continuity of care and promote consistency in breastfeeding support. Such steps will be critical for optimizing early maternal-newborn care and closing persistent gaps in breastfeeding initiation and maintenance.